Tech & Learning Read More

ISTELive and the ASCD annual conference will co-locate starting next year in San Antonio, Texas

Tech & Learning Read More

ISTELive and the ASCD annual conference will co-locate starting next year in San Antonio, Texas

This is K12Leadrs’ summary… The source for this story is originally reported in the Washinton Post, by Laura Meckler, Hannah Natanson and John D. Harden. The original is freely available behind a paywall.

According to a Washington Post analysis of FBI data, hate crimes targeting LGBTQ+ people on school campuses have sharply risen in recent years, climbing fastest in states that have passed laws restricting LGBTQ+ student rights and education.

In the 28 states with restrictive LGBTQ+ laws, the average number of reported hate crimes was more than three times higher in 2021 and 2022 than from 2015 to 2019. Overall, there were an average of 108 anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes at schools reported per year from 2015-2019 on both college and K-12 campuses. In 2021 and 2022, that more than doubled to 232 on average per year.

The rise was even steeper when looking just at K-12 school campuses in restrictive states – increasing from an average of about 28 per year from 2015-2019 to an average of about 90 per year in 2021-2022, more than a quadrupling.

(Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/03/24/lgbtq-students-hate-crimes-data/)

At the same time, calls to LGBTQ+ youth crisis hotlines have skyrocketed. The Trevor Project, which provides crisis intervention, received about 230,000 calls, texts and online chats in the 2021-2022 fiscal year, but over 500,000 the following year. Similarly, the Rainbow Youth Project saw calls rise from around 1,000 per month in 2022 to over 1,400 per month last year, with the top reason being anti-LGBTQ+ “political rhetoric.”

The Post cites examples like 17-year-old transgender student “Carden” in Virginia who faced harassment from classmates calling him slurs and telling him to die. Carden argues politicians’ anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric has shaped adults’ views in his conservative county.

Another example is a transgender teenager in Mississippi whose mother said he faced regular harassment over his appearance, missed weeks of school from bullying-induced breakdowns, and had suicidal thoughts, which she partially attributed to the state’s ban on transgender students playing sports matching their gender identity.

Studies show LGBTQ+ youth are at particular risk. The CDC’s 2021 survey found over a third of gay, lesbian and bisexual students were bullied either on campus or online that year, compared to just 1 in 6 straight students.

Experts say the restrictive laws create a hostile environment and may make students more reluctant to report incidents in conservative states. Advocacy groups argue the laws send a message that LGBTQ+ students are unwanted.

However, the higher per capita rates in liberal states may reflect those places being more likely to report and have policies encouraging it, not necessarily more incidents occurring.

The article highlights the February death of non-binary student Nex Benedict in Oklahoma following an alleged bullying incident as drawing increased national attention. The Rainbow Youth Project saw a crush of calls from Oklahoma that month.

Oklahoma has enacted several laws restricting transgender rights in recent years and is considering further measures this year, which the state’s superintendent of schools supports to counter what he calls “radical gender theory.”

The Post obtained the hate crime data from the FBI’s database using the agency’s public API, filtered for anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes on school campuses. The data is voluntarily reported by law enforcement agencies. The Post also interviewed students, families, advocates and researchers nationwide to report on this alarming trend amid the ongoing wave of legislation targeting LGBTQ+ rights and expression in education.

This story was originally reported by Courtney Tanner of The Salt Lake Tibune

In the ongoing debate over book bans in Utah schools, one district has concluded a controversial review over whether to keep major religious texts like the Bible, Book of Mormon and Quran on library shelves.

The controversy began last December when a parent in the Davis School District filed a complaint arguing the Bible should be removed because it contains vulgarity and violence, citing Utah’s strict new law restricting “indecent” books in schools.

The district initially agreed, determining the Bible was too vulgar for elementary and middle school libraries, though it would remain in high schools. But that decision was quickly reversed amid a fierce backlash from residents and state lawmakers who accused the district of misinterpreting the law and embarrassing the state.

However, the reversal on the Bible didn’t end the book challenges. Shortly after, separate complaints were filed targeting the Book of Mormon, the foundational scripture for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as well as the Quran, the holy book of Islam. The complainants argued those texts also contained inappropriate content like the Bible.

The reviews for the Book of Mormon and Quran took eight months to complete in the wake of the Bible controversy. Finally, in January, the district announced both books would be allowed to remain in all school libraries without elaborating on its reasoning, simply stating the texts do not violate state standards.

The removals have been extremely controversial under Utah’s new law, which requires any book considered “pornographic” be pulled immediately with no exceptions. For other books, committees must weigh whether the overall literary value outweighs any inappropriate content.

Hundreds of titles have already been removed from libraries across the state, with LGBTQ-related books facing a disproportionate number of challenges and bans.

The legislature recently updated the law to make it even easier for books to be banned statewide based on parental complaints. However, advocates are urging Republican Governor Spencer Cox to veto those changes when he receives them.

As the battle over appropriate school library materials rages on in Utah and nationwide, the religious texts have become a new flashpoint in the heated debate.

District Administration Read More

After uproar over its initial decision to ban the Bible — which was later reversed — a Utah school district has been trying to better separate the wheat from the chaff in determining which religious books can stay on library shelves.

And it has decided all of them are good books.

Earlier this year, Davis School District concluded its long pending reviews of both the Book of Mormon, which is the foundational scripture for the Utah-based Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and the Quran, the holy book for Islam. They will remain in schools for any student to check out, a spokesperson for the district confirmed to The Salt Lake Tribune.

Read more from The Salt Lake Tribune.

The post Parents challenged the Book of Mormon, the Quran in this Utah school district. Here’s what happened next appeared first on District Administration.

This story was originally reported for NBC News, By Maya Eaglin and Nicolle Majette

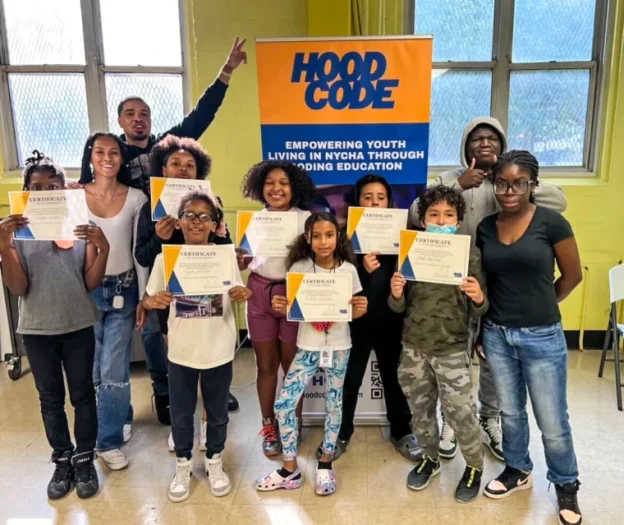

Founder Jason Gibson said Hood Code was designed “to make it easily accessible to the families that live here.”

Tucked away in the red-brick community center of the South Jamaica Houses in New York City is a small multipurpose room filled with plastic chairs and tables. A piece of paper taped on the door shows the schedule for the day, with Hood Code starting at 3 p.m.

Right on time, the quiet room fills with giggles and sneaker squeaks as children pile into the space, each one excitedly talking over the other.

Hood Code is an organization that provides free coding classes to students who live in New York City’s public housing. These apartments are home to more than half a million low-income families and individuals, and 25% of them are under the age of 18.

Founder Jason Gibson said Hood Code was specifically designed to be in these neighborhoods and serve this community.

“I wanted to make it easily accessible to the families that live here,” Gibson said.

The workshops introduce the basics of coding to kids ages 8 to 13, and have so far taught about 300 children in housing buildings throughout the city. The programming also helps them develop problem-solving skills, self-confidence and innovative thinking.

The students primarily use Scratch, a free block-based language program that allows them to express themselves creatively and learn the basics of how professional coders create some of their favorite video games and apps.

Many of the kids embark on quests to make their own video games or re-create their favorites, finding inspiration in games like Flappy Bird and Geometry Dash.

Gibson founded Hood Code in 2019, but the idea for the program was born two years prior — from behind bars.

While serving a five-year sentence, Gibson spent most of his time expanding his knowledge and researching both the tech industry and African American history.

“That was my first opportunity to really sit down and read,” Gibson said. “And I realized how much of a disadvantage I was at and how kids from my neighborhood are in.”

Those disadvantages inspired Gibson to provide his community with opportunities that he says he wished he had growing up.

“I think my life could have possibly been different,” Gibson said. “I’ve always been an entrepreneur, I’ve always had that spirit. I could have been maybe one of the big tech founders.”

Gibson used that entrepreneurial spirit to gather sponsors and community members to ensure that Hood Code would be free for students and a paid job for tutors, many of whom are in high school.

“Coding is not always necessarily accessible to kids that we teach,” Chigo Ogbonna said. She’s a high school senior and a tutor at Hood Code. She and her friend Sara Outar decided to take on the job together.

“I think it’s because we both come from low-income communities, we understand. I didn’t have a computer until basically high school, when I had to do online school. And I didn’t even know that jobs in coding existed,” Outar said.

Black people made up 9% of the STEM workforce in 2021, according to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. A 2021 Pew Research analysis found that Black and Latino adults are less likely to earn STEM degrees than degrees in any other field, and they make up a lower share of STEM graduates compared to other populations.

“I think the passion, the drive that these kids have is something that you don’t see in your ordinary kid, because I know that they had to work 10 times harder to be here,” Ogbonna said.

With $200,000 from The David Prize, a no-strings-attached award given to New York-based innovators that the organization won in 2022, Gibson said he is more determined to continue expanding Hood Code’s programming.

“I wish people knew about some of the creativeness that the students have, the ambitions that the students have, the abilities that the students have, and the interests,” Gibson said. “I think people have stereotypes or their own beliefs about neighborhoods like these in general, and a lot of times they’re wrong.”

This story was originially reported on by Axios Austin and District Administration

Many Texas school districts haven’t hired armed security officers at every campus, as required by a new state law, because of a lack of funding, writes Axios’ Fiza Kuzhiyil .

Why it matters: After 19 students and two teachers were killed at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, the Republican-led Legislature passed new mental health and school safety standards last year.

Catch up quick: House Bill 3, which went into effect in September, expanded and reinforced existing school safety efforts, such as required mental health training.

Between the lines: Gov. Greg Abbott blocked efforts to boost school funding, saying he wanted lawmakers to first pass a bill to provide taxpayer money for private school tuition.

Zoom in: The Austin Independent School District, which currently has more than 80 officers, is hiring more “to comply with the law,” district spokesperson Cristina Nguyen tells Axios.

By the numbers: Two decades ago, 108 school districts in Texas had their own police departments.

What they’re saying: “School district policing is not [like] policing on the streets,” Texas School District Police Chiefs Association president Bill Avera said. “The school becomes the community, and you have to have relationship building.”

eSchool News Read More

Key points:

Making summer reading a year-round project is critical part of a learning strategy

States need to strengthen reading instruction policies

How we can improve literacy through student engagement

For more news on literacy, visit eSN’s Innovative Teaching hub

When I began teaching English as a second language (ESL), I had anywhere from seven to 13 different languages in my classroom because our district was in an area with a lot of recent immigration. It was an entry point for me to begin thinking about what a rich profession teaching is, along with how students develop their early reading skills, especially when they are learning multiple languages at once.

Today, I am the director of Literacy First, a program that the University of Texas launched almost 30 years ago with the mission of teaching students to read in the early grades. Literacy First fulfills its mission by offering a variety of support services, with a particular focus on achieving successful outcomes for growing readers, including one-to-one literacy interventions, teacher and staff training, instructional coaching, data-centered advising, and bilingual and culturally sustaining reading resources and interventions. One of the things I’ve learned a great deal about along the way is how to run an effective summer reading program for emergent bilingual students.

Here are three best practices that are effective regardless of the languages your students speak at home.

1. Encourage students to read at home by embracing their home language.

At Literacy First, we’ve always taught in Spanish. In fact, ours is the only program of its kind in the country that does early reading intervention and Tier II instruction in Spanish. We know from a couple decades of research that when children learn to read in their primary language, they are able to learn to read in additional languages more effectively.

If a teacher works on foundational skills such as phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, decoding, fluency, and comprehension in Spanish with a student who is more comfortable in that language, those skills will transfer, building better English results over time and offering that student all the amazing assets that come with being bilingual.

It’s also important to remember that the majority of emergent bilingual students in the United States are actually simultaneous language learners already. Many of them were born in the U.S., and all of them now live here in this English-oriented country. Most of them aren’t starting from zero, so I suggest a nuanced approach to thinking about the strengths students bring with them. What is their full linguistic repertoire? How can we assess and understand those strengths across languages to teach more effectively? Ultimately, it means understanding that bilingualism is the goal rather than English proficiency alone, and that means there is no hurry to jump to English without instruction in other languages. Students will make progress—even on their ability to read in English—as they develop their home language skills.

Students in Texas schools speak more than 120 languages, with 88 percent coming from a Spanish language background. Beyond formal summer school that teaches multilingual development and encourages families to nurture home languages, access to books in those languages or books that reflect students’ cultural backgrounds (such as those in the Capstone virtual library) can also support their reading development.

2. Provide a constantly refreshed diet of new books.

When I worked at Austin Independent School District, we really latched onto this study from literacy intervention expert James Kim that found students in grade 6 could beat the summer slide by reading just five books over the summer. Today in Austin, there’s still a campaign telling students and families to “Beat the summer slide, take the 5 book dive,” as they distribute books all over the city. Even that small number of books has a big impact, especially for students who don’t have access to enrichment opportunities.

If you’re looking at younger students, however, they really need more like five books each week, and they need to be voraciously gobbling down those books. They need appropriate reading material at their fingertips in any way possible. Sixth graders need chunky chapter books, but younger kids are going to read books that are sometimes just two or three dozen pages long. I also see with my own younger children that when we get back from the library, only 10 of the 20 books we brought back are actually interesting to them, and sometimes only one is engaging enough to read with a parent and then later on their own. Younger children really need a constantly refreshed diet of new books.

Weekly trips to the library are a great way to give them new books, but not all parents have the time or opportunity to visit the library regularly. Digital libraries are also an excellent solution that doesn’t require anyone to leave the house. My kids’ school district offers PebbleGo, which they love because it has a huge selection of books and articles, and because it provides built-in support, such as word definitions and the ability to switch between English and Spanish.

3. Build in touchpoints to maintain momentum.

It’s important to build excitement about your summer reading program before school is out. No matter how well that goes, however, students’ reading momentum will slow down after the first few weeks of summer. To keep students and their families focused on reading, be sure to have a few touchpoints planned. Mailing out a few more books is a great option, and a book bus that travels around the district can be a fantastic way to bring members of the school community together during the summer. Teachers who have strong relationships—and shared language backgrounds—with their students can be instrumental in encouraging and inspiring them to read over the summer by sending planned messages or convening events. However, teachers’ efforts should be compensated and supplemented by school, district, and community support.

When I was with Austin ISD, we partnered with a local bookstore that did some promotional work for us and offered discounts to families. We also partnered with the libraries within the district as well as a digital library provider to ensure students had a vast library at their fingertips, no matter where they were. The donations and other help from those partners were really instrumental in making our summer reading programs work.

Finally, many schools wait until spring to plan their summer reading program, but making it a year-round project is the most effective way to make sure your students have as many books as you can get into their hands, give yourself time to build excitement, check in to maintain momentum, and help all of your students avoid the summer slide, no matter what language they speak at home.

This story was originally published on Mirror Indy, and can also be found on The74.org

For many families, building a home library can be a challenge – especially when kids have different reading interests and abilities. But one Indianapolis mom named Jessica Davis has found a creative way to cultivate her children’s love of reading through a grant program.

Davis has three kids – a bookworm daughter who devours multiple books at once, one son who avoids reading, and another son with autism who needs extra stimulation. To engage each of them, Davis has filled her home with all kinds of books – chapter books, picture books, fantasy novels, sports biographies, and stories featuring successful Black heroes.

But purchasing over 200 books for a home library is no small expense. That’s where The Mind Trust, a local nonprofit, came in. Over the past four years, the organization has provided small literacy grants from $500 to $5,000 to dozens of families in Indianapolis.

Davis received two rounds of funding totaling $4,500. She used the money to build out a cozy reading nook with beanbags, rugs, and shelves – creating an inviting space to spend time with books. She carefully selected titles to reflect her family’s cultural backgrounds and interests.

The grants have allowed Davis to accelerate her home literacy efforts in a way that would have taken years to accomplish on her own limited budget. And it’s paying off – Davis says all of her kids’ reading scores have improved significantly.

Kateri Whitley from The Mind Trust emphasizes that the Go Farther Literacy Fund isn’t just about skill-building. “It’s building community,” she says, by giving families resources to cultivate reading as a shared experience.

For Jessica Davis, that means opening up her home library to neighborhood kids without access to many books. Her hope is to continually refresh her collection through future grant cycles, creating an oasis for children to discover the joy of reading.

As states like Indiana work to improve stagnant literacy rates through tutoring programs and policy changes, grassroots efforts like these home libraries provide another innovative model to help get kids hooked on books.

This summary is based on an article by F. Chris Curran as published in The Conversation Read More

From time to time, elected officials facing increased violence or unrest suggest calling in the National Guard for assistance. Recently, officials in Brockton, Massachusetts took the unusual step of requesting the National Guard be deployed to Brockton High School to help address student fights, drug use, and disrespect toward staff.

As a researcher who studies school discipline weighs in, this situation is part of a broader national trend of schools struggling with perceived increases in student misbehavior since the COVID-19 pandemic. While the National Guard has been utilized in educational settings before, the history is mixed.

In 1957, the Arkansas National Guard initially blocked nine Black students from integrating into an all-white high school in Little Rock, before eventually being ordered to enforce desegregation weeks later. More tragically, in 1970 the Ohio National Guard fatally shot four students during protests at Kent State University over the Vietnam War.

More positively, during the pandemic the New Mexico National Guard helped fill teaching vacancies, receiving generally favorable reviews. And after the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting, there were proposals to fund using the Guard for school security, though this did not pass.

School officials in Brockton argue the Guard could provide much-needed staffing support to address behavior issues. However, the researcher raises concerns that a military presence, even temporary, may escalate situations or make students feel less welcome. Research shows effective teaching, positive school environments and relationships are key for safe schools.

The increasing militarization of schools, fromGrenade launchers for school police to data linking officers to higher suspension and arrest rates, underscores these worries over a National Guard deployment.

Ultimately, the researcher believes calling the National Guard is treating a symptom, not the root causes of misbehavior. What schools truly need are more teachers, counselors and mentors to build supportive, educative environments for students.

With Massachusetts’ governor rejecting the National Guard request, the Brockton High situation highlights the challenges facing many schools post-pandemic. But as critics like the NAACP argue, a military response is unlikely the solution students deserve.

District Administration Read More

Maine was one of the first states to pass legislation providing free school lunches to all students after pandemic-era funding expired – a policy that has been adopted in seven other states and is being considered across the country.

But since the law took effect a year and a half ago, some districts have struggled with an unintended consequence: Now that parents no longer need to fill out applications to get their children access to free meals, officials have lost an important source of data on their district’s low-income households – information traditionally used for funding.

The free and reduced-price meal application, a federal form sent home with students at the start of the school year, allows districts to determine what percentage of students qualify for free or reduced-price meals.

Read more from the Portland Press Herald.

The post All Maine students now get free school lunches. What does that mean for poverty data? appeared first on District Administration.

District Administration Read More

Virginia high school teacher Joe Clement keeps track of the text messages parents have sent students sitting in his economics and government classes:

— “What did you get on your test?”

— “Did you get the field trip form signed?”

— “Do you want chicken or hamburgers for dinner tonight?”

Clement has a plea for parents: Stop texting your kids at school.

Parents are distressingly aware of the distractions and the mental health issues associated with smartphones and social media. But teachers say parents might not realize how much those struggles play out at school.

The post Why parents should stop texting their kids at school appeared first on District Administration.